The horizon, where sky meets earth, will always be at the artist's eye level, regardless of how high, low, or to the left / right the artist is positioned.

Most items positioned in relation to that horizon line will be in two point perspective but there can be multiple items in a picture, each with their own single point, or, set of two points.

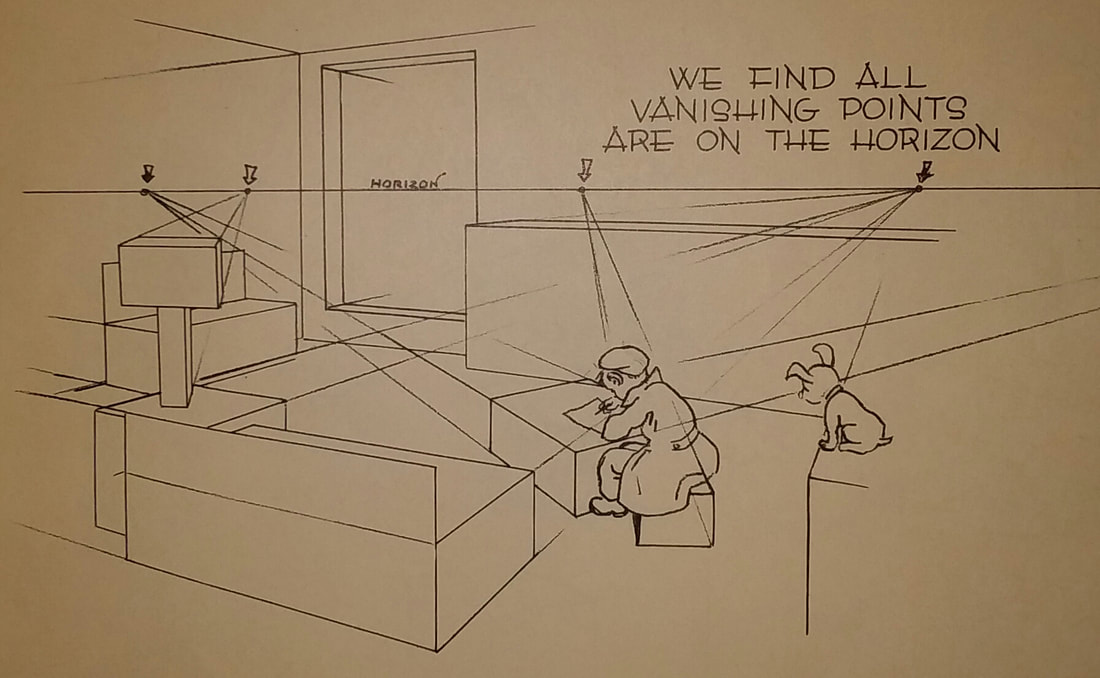

Look at the diagram below, by Ernest Norling, and notice how the lamp-like object over on the left is nearly entirely presented in ONE point perspective, while the couches and end tables are in TWO point perspective, sharing those points on the horizon line, one visible to us, on the right, and the second lying outside the picture plane, on the left.

There is a figure of a person seated at a coffee table rendered in its own two point perspective position, with, finally, their stool upon which they sit rendered in one point perspective.

Most items positioned in relation to that horizon line will be in two point perspective but there can be multiple items in a picture, each with their own single point, or, set of two points.

Look at the diagram below, by Ernest Norling, and notice how the lamp-like object over on the left is nearly entirely presented in ONE point perspective, while the couches and end tables are in TWO point perspective, sharing those points on the horizon line, one visible to us, on the right, and the second lying outside the picture plane, on the left.

There is a figure of a person seated at a coffee table rendered in its own two point perspective position, with, finally, their stool upon which they sit rendered in one point perspective.

It can be tricky to accurately assess the horizon points which lay outside a picture plane. You may need to use various tools such as a yard stick, a pin stuck in the wall, etc.

The vertical lines have no vanishing point, they're just straight up and down.

Three point perspective is not used quite as frequently but familiarize yourself with it for those sky high, bird's eye views of the city (think Iron Man flying down, looking down on New York's building roofs and the vertical lines of the buildings all converging on a single point, envisioned below the street surface) or a bug's view of a giant towering structure.

There is no automatic indicator for the artist, telling them how far to the left or right to station points onto the horizon line, in two point perspective (haste in dropping in objects in perspective can cause them to appear squished or too stretched and just plain odd in relation to each other) so the beginner is advised to sketch from observed environment and employ perspective afterward, to tighten up the sketch, as an exercise.

A handy way to make many images on paper look three dimensional is to imagine that they are contained within boxes. A lot of things one draws can be envisioned this way. And learning to draw a box in realistic perspective is quite easy. So imagine your subject boxed - in correct perspective (often "TWO point" but it could be one point) - in relation to your eye's horizon line.

Look at your environment and try sketching it, at least the area roughly six feet in front of you and eight or ten feet to the left and right, observing the edges of tables, chairs and so forth, and notice how they all head toward a horizon line, regardless of whether you can see the horizon line. If there are other objects within this area, image them in boxes, with the boxes' edges similarly converging at their point(s) on the horizon.

The vertical lines have no vanishing point, they're just straight up and down.

Three point perspective is not used quite as frequently but familiarize yourself with it for those sky high, bird's eye views of the city (think Iron Man flying down, looking down on New York's building roofs and the vertical lines of the buildings all converging on a single point, envisioned below the street surface) or a bug's view of a giant towering structure.

There is no automatic indicator for the artist, telling them how far to the left or right to station points onto the horizon line, in two point perspective (haste in dropping in objects in perspective can cause them to appear squished or too stretched and just plain odd in relation to each other) so the beginner is advised to sketch from observed environment and employ perspective afterward, to tighten up the sketch, as an exercise.

A handy way to make many images on paper look three dimensional is to imagine that they are contained within boxes. A lot of things one draws can be envisioned this way. And learning to draw a box in realistic perspective is quite easy. So imagine your subject boxed - in correct perspective (often "TWO point" but it could be one point) - in relation to your eye's horizon line.

Look at your environment and try sketching it, at least the area roughly six feet in front of you and eight or ten feet to the left and right, observing the edges of tables, chairs and so forth, and notice how they all head toward a horizon line, regardless of whether you can see the horizon line. If there are other objects within this area, image them in boxes, with the boxes' edges similarly converging at their point(s) on the horizon.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed